Think-Piece: The Neglected Intellectual Legacy of '1968'

Couze Venn

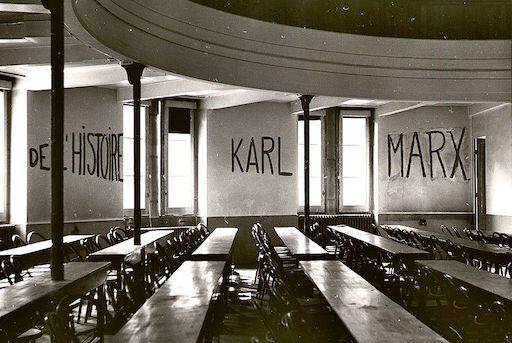

Image: University of Lyon graffiti made during student occupation of parts of the campus during May 1968 events in France. Source: Georg Louis, Wikipedia CC BY-SA.

As to be expected, the 50th anniversary of May 68 has generated a mass of comments and stories which highlight the familiar events that mark out the broad political and cultural context for what was going on at the time. Yet, surprisingly, one really important aspect has been curiously neglected. It concerns the intellectual and radical legacy of these events and, as I shall argue, it is this legacy which abides though it is now more than ever threatened.

As one would expect, most of the accounts have stressed both the range and global character of the radical movements and struggles that had sprung up in the 1960s in opposition to existing relations of power; they are clearly central for understanding the necessary background for May 68. Indeed, many commentaries have underlined the fact the atmosphere sustaining radical change during that period was the product of a whole cluster of events, particularly, the Civil Rights and anti-racist movement, the anti-war protests about Vietnam, the beginning of second wave feminism, and the emergence of a counterculture. And we all remember that 1968 was the year that saw the assassination of Martin Luther King in April and the disturbances that followed in cities across the USA, the Tet offensive in Vietnam that ended American Cold War regime change in that country, the Prague Spring uprising against Soviet Union domination, the assassination of Bobby Kennedy in June, the Tlatelolco massacre in Mexico City in October that stands as yet another sign of the violent suppression of left-leaning radicalism, and the Black Power salute at the Olympics Games in October that stood as a symbol of the continuing struggles against racism.

A wider picture would include the execution of Che Guevara in October 1967, widely seen as the signifier exemplifying the ongoing neo-imperialist interventions against the possibility of socialist revolution in Latin America in the wake of Cuba and other socialist initiatives in the ‘Third World’. 1967 was also the start of the troubles in Northern Ireland and the Six-Day Arab-Israeli war, though the big picture of uprisings and dissidence would include anti-colonial wars in many parts of the world, Black Power (from 1965) and Black Panther Party (from 1966) anti-racist campaigns in the USA, anti-Apartheid struggles in South Africa. And we were in the midst of the Cultural Revolution of China, an event with quite wide repercussions. It was really kicking off everywhere. At the heart of this situation were projects of emancipation or liberation aimed at dismantling the structures that support oppressions based on race, gender, class. Optimism and determination animated these initiatives, as well as a sense of a common foe. For many, capitalism was seen to be the driving force sustaining these structures, though of course asymmetrical power relations, notably patriarchy, operated, and still operate, through other authorising means as well, such as by appeal to religion or ‘tradition’, or even biology. This common target helped to forge a sense of solidarity, informed at the level of theory by a broad Marxism.

In terms of the wider contextualisation of May 68, many have noted the counterculture that embodied the spirit of rebellion against the hypocritical values and norms of what was thought of as ‘bourgeois’ morality at the time. For the mass media, and in popular memory, the counterculture has been subsumed under the banner of ‘sexual liberation’ and the ‘permissive’ society, though the truth is that, whilst it was quite diffused and uneven as a phenomenon, it encapsulates the surge of an oppositional culture that was present across the arts and literature, music, theatre, film, fashion, and that included a mixture of rock, folk and blues music, radical films such as The Battle of Algiers (1966) or those of Godard, Rochas and others, and generally a profusion of innovative works that rejected conventions and promoted radical perspectives on class and other oppressions . It also found expression in underground magazines such as Black Dwarf, Ink, OZ, IT (or International Times). And it was echoed in early feminism, and revolutionary or anarchist thought as expressed say in France by the Situationists, notably in the writings of Guy Debord and Raoul Vaneighem that also informed May ‘68.

But what I want to draw attention to in this piece is the explosion of theoretical work that followed in the wake of ‘1968’, energised by the can-do spirit of change that drove the younger generation of intellectuals and activists. In particular I will foreground the birth of a mass of journals that became the organs through which crucial shifts in perspective were worked out, and that found an echo in the emergence of new forms of resistance, particularly the challenge to the hegemony of capital, and the challenge to the physical, psychological, ontological and epistemological violences that are intrinsic to racism, patriarchy and neo-imperialism. Their effects became widespread and have reshaped radical thought on the left ever since.

We should perhaps remember that one of the immediate aftermath of ‘1968’ was a general disappointment that revolution by democratic means hadn’t worked, especially as communist parties and most workers organisations failed to provide the level of support or the broader-base analysis that it was hoped they would do. For some it fed into a kind of nihilist despair that led to the violent campaigns of the Red Brigade in Italy from 1970, the Baader-Meinhof faction in Germany in the same year, the Weathermen (or Weather Underground, 1969) in the USA, the IRA in Northern Ireland. At the same time, it marked a gradual distancing from orthodox or institutionalised Marxist analyses, a shift that found an outlet in, for instance, dissident readings of Capital (notably by Louis Althusser and colleagues), or the setting up of Workers Power movements in France and in Italy (though Autonomism there started earlier); they were projects aiming to renew socialist politics outside the established parties.

A look at the journals and magazines that emerged from the early seventies show the diversity of political and theoretical concerns. Amongst the early starters we find Radical Philosophy, the feminist publication Spare Rib, Undercurrents (an environmentalist magazine), and Gay News, all from 1972. Race & Class followed in 1974, and (socialist) History Workshop in 1976. A cluster of journals appear from 1977: Capital & Class, Ideology & Consciousness, Radical Science; then M/F (feminist journal) in 1978, Feminist Review (1979), Subaltern Studies from 1979. In France the newspaper Libe’ration started publication in 1973, and Actes de la Recherche (associated with Pierre Bourdieu) in 1975; other significant journals such as Theory, Culture & Society (1982), Hypatia (1986), Red Pepper (1987) New Formations (1987) were later developments that fed from the same stream.

This theoretical renewal clearly reflected the various constituencies on the left, notably, second wave feminism and women’s liberation in Europe and the USA, socialism, anti-racism, anti-colonialism, environmentalism, and the challenging of sexual norms. I should mention the work of the Birmingham Centre for Cultural Studies from 1964 and its occasional papers from 1968 (when Stuart Hall became Director) that covered the whole range of issues which the publications I’ve noted addressed.

As to be expected, a wide spectrum of perspectives was developed across these publications, reflecting the diverse theoretical and political projects associated with movements addressing racism, feminism, environmentalism, socialist history, and the problematisation of a whole history of thought that had been authoritative up to the 1960s. And it was ‘1968’ as the kind of global and wide-ranging event that I have outlined that had incited interest in the critiques going on at the level of theory in places like France, Germany, Italy, the USA, South America, India in the hope of finding approaches that could provide inspiration for the new departures that many felt had become necessary.

The issues that became the target for problematisation, or that emerged to alter the theoretical and political agenda reflect the concerns that arose in relation to ‘1968’. Looking back it is clear that behind the various initiatives one can detect the longer and perennial struggle for equality, social justice, fundamental rights, liberty. It could be argued that for that reason the conceptualisation of power stands out in the debates, notably in terms of a more subtle analysis of the mechanisms and practices through which state power is exercised, specifically by reference to the inscription of power in discourses that authorise hegemonic regimes and modes of exclusion such as racism, and circumscribed the norms of the ‘normal’ - Michel Foucault’s and Antonio Gramsci’s analyses gained traction for that reason. The challenging of patriarchal power by feminists added another dimension to the problematic of power by foregrounding the mix of personal, cultural, social and institutional elements that participate in constituting the subjectivities and practices involved in the subjugation of women. The rethinking that was part of the renewal of radical thought focussed on these discourses, practices and mechanisms themselves to uncover their mode of operation and inform oppositional activity.

Too many names come to mind that a list would fail to do justice, encompassing ‘French Theory’, the Frankfurt School, the work of neo- or post-marxists and the great outpouring of writings from feminists and anti-racist and decolonial activists everywhere - I confess I drew up a list that grew to be too extensive. In any case it was so diverse that it is easy to misrepresent. Indeed, the range of journals and radical publications reflect this plurality of projects – though interestingly efforts to coordinate interventions and thinking across different constituencies did take place, for example in terms of the cooperative distribution of radical publications in the UK, or through the search for common ground ‘beyond the fragments’ – to echo the title of the book by Sheila Rowbotham, Lynne Segal, and Hilary Wainwright.

Looking back, and trying to locate the analytical work from the 70s, what is interesting is the geo-political landscape that functioned as background. In particular the renewed determination of the USA and allies to smash all attempts to establish socialist regimes in mainly postcolonial countries to start with. The list of places where the USA and allies intervened to destabilise or overthrow left-leaning governments is staggering. Besides Indochina and the Middle East, the consolidation of capital saw the overthrow and killing of Allende in Chile (1973), ‘regime change’ in Argentina, Brazil, Guatemala, Pakistan, Afghanistan amongst the notable examples, and a new stage of globalisation characterised by the growth of finance capitalism and corporate power. The ongoing effects on the geopolitical landscape sadly abide in the conflicts they triggered.

It was also a time when, after the fright of ‘1968’, the right regrouped in the form of neoliberalism (the Reagan/Thatcher axis from the late 1970s), whilst the Chicago Boys followed regime change with programmes of ‘liberalisation’, marketisation and deregulation targeting state social welfare apparatuses and the privatisation of commons. When viewed against this wider background of struggles for social justice, neoliberalism itself can be regarded as not so much an economic doctrine as a political project whose aim is the promotion of capitalism against the possible advances of socialist politics.

So, when we look at the wider landscape of post 1968 in which critical theory blossomed, we become aware of the complicated, global and cosmopolitical situation in which theory tried to intervene. Unfortunately too often theory became ghettoised, whilst institutional pressures have managed to incorporate some academic innovations that fostered radical programmes of study - say cultural studies, women’s studies or Black studies - though many of these are now under threat by corporatised universities. And many movements on the ‘left’ have become diluted by the kind of identity politics that lets itself slips into exclusionary politics of one kind or another, such as nationalism, ethnocentrism, and the privileging of individualist projects that undermine attempts to forge bonds of solidarity across constituencies.

Yet, this is happening at a time when the need to find common ground has never been more urgent given that our times are marked by creeping fascism, the normalisation of fundamentalisms, total surveillance to curb liberties and rights, the consolidation of counter-emancipatory ideologies, and failure to seriously tackle impending disasters resulting from climate change, resource depletion and widespread damage to ecologies on land and in the oceans. Perhaps the spirit of 68 is being reanimated in movements such as Occupy, Podemos, Black Lives Matter, or in the extension of the idea of common pool resources such as with the idea of creative commons. What is certain is that the search once more for common ground in support of an emancipatory and cosmopolitical politics beyond the fragments and beyond capitalism requires even greater courage and commitment than at any time in recent memory.

Note

This is a slightly amended version of an article that originally appeared in openDemocracy on 12th July 2018.

Couze Venn is Professor of cultural theory and postcolonial theory at the Centre for Cultural Studies and Associate Research Fellow at the University of Johannesburg. He is also a managing editor of Theory, Culture & Society, and one of the editors of Body & Society. His current research concerns the search for postcapitalist alternatives to neoliberal capitalism in the context of converging crises affecting economies, climate, essential resources, the quality of the environment, and growing inequalities.