Review: Sean Cubitt, ‘Finite Media: Environmental Implications of Digital Technologies’

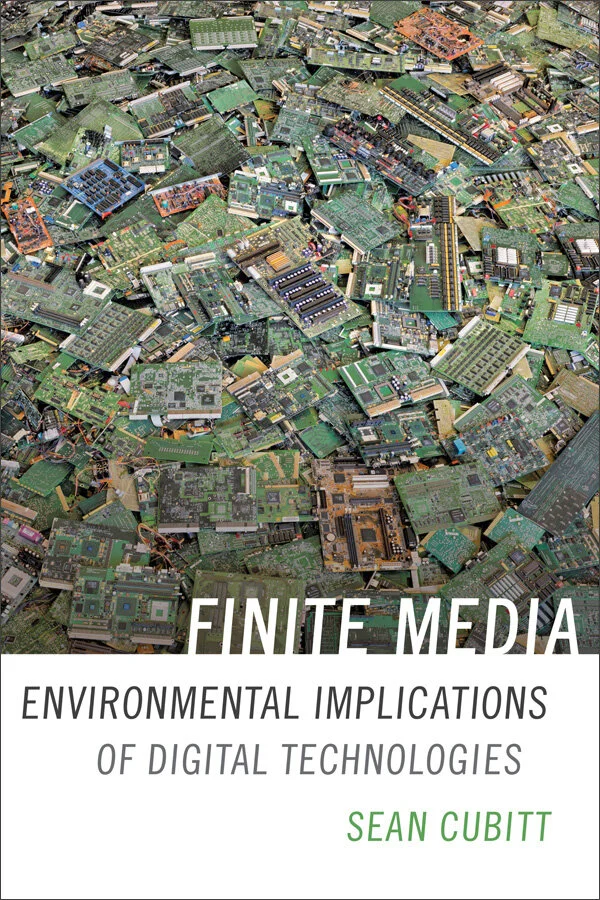

Review of Sean Cubitt’s Finite Media: Environmental Implications of Digital Technologies (Duke University Press, 2017), 256 pages.

Abstract

Finite Media: Environmental Implications of Digital Technologies moves across a vast terrain of social and political thought to assemble a critical study of the linkages between digital technologies and environmental degradation. It stands as a “meditation on mediation” and communication as a critique of humanity’s “obsessive accumulation of everything” from earth’s finite resources considered through the over-production and consumption of humanity’s love affair with the ‘digital.’ The book makes a substantive intervention in contemporary debates and analyses about the current state of the environment and argues for a politics rebuilt on aesthetic principles that hinges on a rethinking of the ways human beings communicate—and commune—with each other, but also with nature in the sense of a relational understanding of how what we do, what we take, and what we make on this planetary world is deeply interconnected.

Reviewed by Sandra Robinson

Sean Cubitt’s Finite Media: Environmental Implications of Digital Technologies is so much more than the title suggests: it is a meticulously researched and thoughtful intervention into the linkages between digital media and environmental degradation. A genealogical journey that is a “meditation on mediation” and communication as a critique of humanity’s “obsessive accumulation of everything” from earth’s finite resources considered through the over-production and consumption of digital media (7). It is a book, Cubitt writes, which explores how humans can authentically ask the question of “how to live well” without first confronting “how it is that we live so badly” (15). The answer to those questions demands we turn our attention to politics and aesthetics, and, as Jacques Rancière argues, to account for the “distribution of the sensible at stake in any politics,” which is to say the ability for individuals to see and say and to perceive, think, and act in the world (2011: 12). For Cubitt, this means attending to both “perception … and art, the techniques of mediation and communication in which we construe our relations with one another and the world” to overcome, he argues throughout the book, the “distinction between human and environment” (15, 180). The book contends with, first and foremost, the ecological consequences of communication enabled by and through digital media and the devastating toll on people and our global environment generated by the endless cycle of mining, manufacture and disposal of electronic products. Cubitt’s work fits broadly within media and communication studies, but he has produced a truly original synthesis that brings political economy, media theory, and philosophy together and makes, I argue, a contribution to the burgeoning interdisciplinary field of environmental humanities. He has also very neatly complicated critical media infrastructure studies with a carefully assembled eco-critique that follows from and extends related studies on the materiality of media in work such as Jennifer Gabrys’ examination of “digital rubbish” and electronic waste (2010), Jussi Parikka’s genealogies of media that also engage with substantive environmental impacts (2011; 2015), and Elizabeth Grossman’s exploration of “high tech trash” and the link between toxic materials and human health (2007). Cubitt’s ability to turn over the soiled history of colonialism, industrialization, and neoliberalism in the context of what it takes (and what was taken in the past) to feed our contemporary obsession with everything digital is matched by an equally riveting theoretical and philosophical synthesis that far extends a Marxian political economy critique into wider social and political thought.

Cubitt’s book engages the reader in an ecological media theory at the outset using Charles Tait’s film, The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906) of which 17 minutes of stock still exist, as an example of a ‘living medium.’ This film, originally shot on nitrate stock, is literally decomposing and against this rapid decay film archivists have raced to salvage the remnants with both material and algorithmic interventions to preserve the physical artefact and create a digitally augmented copy. The film itself tells the story of the Australian ‘bushrangers’ known as The Kelly Gang and Cubitt uses the film as a lifting off point to trace out the entanglement of people, places, processes, and things that become comingled in mediation. Mediation as material forces “connecting human and nonhuman events” from the representations of people and places in the film to the nitrate film stock itself, and from the film’s material decay to various digital interventions that signal mediation as a kind of “primal connectivity” between “human, technological, and organic worlds” (2-4). Cubitt then traces this primal connection through four chapters: energy, matter, eco-political aesthetics, and ecological communication as politics. The book concludes with a short rumination on the Cassini-Huygens orbiter, which Cubitt uses as another brilliant example to keep the politics of media, its ideological goals and environmental impacts, in clear focus. His commitment to assembling an eco-political aesthetics through classical Marxism, post-colonialism, and critical social and political theory means that across the chapters, Cubitt is relentless in pulling apart the industrial flow of materials, precarious labour, manufacturing processes, regulatory structures, trade conventions, and waste disposal programmes with case studies that make visible the dirty materiality of digital media.

In chapters one and two, Cubitt links the explanation of ‘finite media’ to the reality of earth’s finite resources, matter and energy, required for digital technologies. The book is organized to move from this discussion of energy and matter, of fossil fuels and nuclear power, to the materials, manufacture and waste recycling of the digital media life cycle, and then into the theme of ecology as mediation. At the forefront of these two chapters is persistent attention to the devastating history of colonial expansion and expropriation in relation to our contemporary environmental crisis. At each turn, Cubitt highlights how ruthlessly the extractive industries have mined and hollowed out indigenous lands in service to global demand for the materials necessary to manufacture digital devices and digital technologies more broadly. The global poor suffer at a scale beyond the reckoning of the global rich and Cubitt systematically draws the link between the “political economy of capital and the specific ideologies of neoliberalism” that only serve masters of industry and markets (30).

There are many lines of thought that work their way through Finite Media, however, two key themes emerge in the middle of the book, which build from the author’s intensive analysis of the global flows of materials, processes, and people necessary to sustain the infrastructure and devices for digital media and the neoliberal indifference to human welfare and environment. In fact what is made very clear in Cubitt’s theoretical analysis is that neoliberalism has bred contempt for the environment, as Isabelle Stengers has put it, and that “it is becoming urgent to create a contrast between the earth valorized as a set of resources and the earth taken into account as a set of interdependent processes” (2011: 163). It is worth noting that Stengers comment was in relation to Alfred North Whitehead’s proto-ecological stance evinced in his concern for the lack of aesthetic values during rampant industrialization in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (1925: 196). Fast forward to 2017 and Cubitt carefully assembles an eco-political media aesthetics that seems, in part, to respond, albeit perhaps unintentionally, to Whitehead’s earlier lament. Cubitt, throughout Finite Media, is arguing for a “politics rebuilt on aesthetic principles” that hinges on a rethinking of the ways human beings communicate—and commune—with each other, but also with nature in the sense of a relational understanding of how what we do, what we take, and what we make on this planetary world is deeply interconnected. This is not an entirely new way of looking at the environmental crisis affecting our planet and people, but it serves to remind us that we cannot necessarily use economic, technological, or even social responses to solve this crisis without a sustained and inclusive political commitment to change. Cubitt’s theoretical and philosophical argument carries with it the echo of Donna Haraway, and although he does not engage her work directly in this book, there are grim references to a ruling class of corporate cyborgs as “biocomputer hybrids.” Recall Haraway’s “The Promises of Monsters” in which she pointedly addresses how “nature for us is made, as both fiction and fact,” following a long and fraught relationship with nature as ‘other’ within colonialism (2004: 64), and this demands a recognition that “[w]e are all in chiasmatic borderlands, liminal areas where new shapes, new kinds of action and responsibility, are gestating in the world” (90). From my view, Cubitt’s careful diagram of the material flows of finite media show us how to not only navigate the borderlands, but what kinds of actions and responsibility are required to confront the environmental crisis. While Haraway’s invocation compels us to action through articulation with and between humans and nonhumans, Cubitt shows us the way through communication because “[i]n communication—and mediation more broadly—the potential of the ages lies, coiled up in them like a spring. The fundamental political task is to build a communicative event embracing the whole world, not just the human” (184). It is also imperative, Cubitt argues, to account for the inhuman actors such as corporations and political elites who frustratingly back away from serious and sustained engagement with the ‘wicked problems’ of environmental degradation.

While the shadow of the Anthropocene looms over Cubitt’s work, he does not explicitly use this term or engage with the idea to frame his critique of digital technology’s role in the global environmental crisis. Clearly the problems Cubitt discusses are relevant to wider debates about whether we are in a new epoch in which human activity has had an impact at the stratigraphic level of the planet’s geological plane of existence. If ecological communication can help us “become wholly environmental” (188) it might be fruitful for Cubitt’s media-aesthetic approach to be considered by other scholars within the environmental humanities who are exploring the Anthropocene. For example, recent analysis in a special issue of Theory, Culture & Society entitled Geosocial Formations and the Anthropocene, featured work in dialogue with Cubitt’s transdisciplinary synthesis. As Nigel Clark and Kathryn Yusoff (2017: 8) note in their introduction to that special issue, “it is the thresholds where the social meets the geologic, the inorganic, the inhuman, that are up for negotiation,” which echoes Cubitt’s concern for eco-political aesthetics that challenge entrenched modes of thought and habits of action in the context of negotiating a better future for our shared earth environment. For Cubitt, “[e]nvironmentalism is a populism: a constantly reformulated demand for better, different ways of being and becoming” (200). Ecological communication is not simply about communicating through a rich media ecology, but about “remembering the materials that media are made of” (11) to craft a media aesthetic that communes with and through our planetary commons.

References

Clark, N and K Yusoff (2017) Geosocial Formations and the Anthropocene. Theory, Culture & Society 34(2–3) 3–23.

Gabrys, J (2010) Digital Rubbish: A Natural History of Electronics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Grossman, E (2007) High Tech Trash: Digital Devices, Hidden Toxics, and Human Health. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Haraway, D (2004) The Haraway Reader. New York and London: Routledge.

Parikka, J (2011) “Introduction: The Materiality of Media and Waste.” In: Parikka, J. (ed) Medianatures: The Materiality of Information Technology and Electronic Waste. London, UK: Open Humanities Press.

Parikka, J (2015) A Geology of Media. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Rancière, J (2011) The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. (trans.) Gabriel Rockhill. London and New York: Continuum.

Stengers, I (2011) Thinking with Whitehead. trans. Michael Chase. Cambridge, MA and London, UK: Harvard University Press.

Whitehead, AN (1925) Science and the Modern World. New York: Macmillan Company.

Sandra Robinson teaches in The School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. Current research looks at algorithmic culture, software simulation, and computational media through the concept of a ‘vital network’.

Email: sandra.robinson@carleton.ca